Craniomaxillofacial Case Documentary

Chen Lee, M.D., FRCSC

Chairman, Division of Plastic Surgery

McGill University

Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Examination revealed a depressed left malar eminence, premature occlusion of the left dental molars, and tenderness along the left maxillary lateral buttress to intraoral digital palpation. Visual examination was normal.

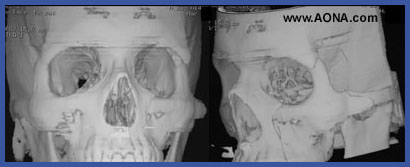

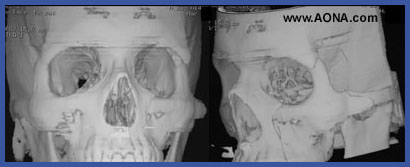

CT images (figures 1-8) revealed a left base of the skull fracture with the greater wing of the sphenoid bone still in continuity with the depressed left malar bone and roof of the orbit. A vertical fracture extended inferiorly from the orbit to the interdental space between the first and second premolar teeth of the left maxilla.

b) Anatomic repair of all fractures would obviate salvage

procedures for the facial fractures but do entail

significant risk of optic nerve and intracranial injury.

c) The author performed a lateral orbital wall osteotomy with selective antomic repair of the extracrainal components of the facial fractures. The depressed intracranial base of the skull fracture was stable and left undisturbed. The malar eminence and maxillary fractures were liberated from the intracranial portion of the fractured greater wing of the sphenoid by osteotomizing the lateral orbital wall through a coronal incision (figures 9-11). Mobilization and reduction of the anterior orbital cone through a lower eyelid incision (figure 12-13) and the maxilla through an upper buccal sulcus incision could then be achieved without disturbing the depressed but stable greater wing of the sphenoid fracture. Enopthalmos was prevented by using titanium mesh to repair roof of the orbit as well as to repair the defect created at the lateral orbital wall osteotomy (figures 14-16).

Facial fractures with an intracranial extension must be always evaluated to determine the sequelae that may result from manipulation required to reduce and repair a fracture. In the case presented, anatomic repair of the orbitozygomatic complex would have jeopardized injury to the optic nerve and risked an intracranial misadventure. This was obviated by liberating the extracranial fracture components from the stable intracranial extension with a lateral orbital wall osteotomy, followed by selective reduction and repair of the extracranial fractures.